Louisville Water will celebrate 165 years in the fall. As we manage through one of the top 10 floods in our history, we’re reminded of Louisville Water’s perseverance through nature’s wrath, never losing sight of the commitment to deliver high-quality drinking water.

Louisville Water will celebrate 165 years in the fall. As we manage through one of the top 10 floods in our history, we’re reminded of Louisville Water’s perseverance through nature’s wrath, never losing sight of the commitment to deliver high-quality drinking water.

That dedication is especially evident in times like these, when you consider the long hours our employees put in to keep the pumping stations running, operations going, and Louisville Pure Tap® flowing.

Lead Operator Brian Farmer was one of the first “hands on deck” in the group assigned 24-hour shifts at the pumping station at Louisville Water Tower.

“We actually drove in on Saturday, but we had to take a boat out on Sunday,” Farmer said.

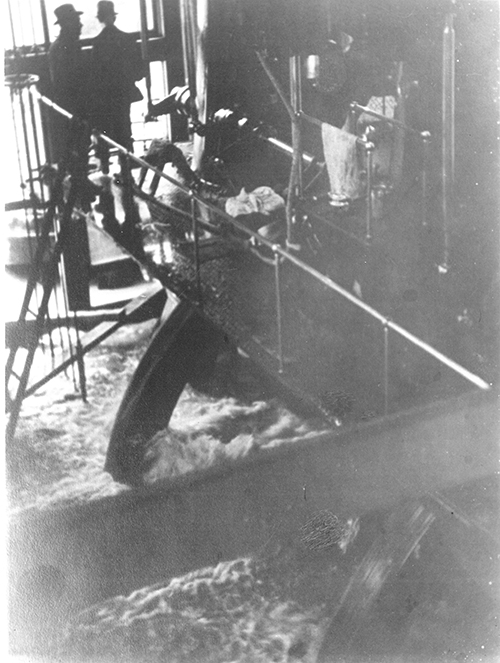

Paired up with a plant maintenance mechanic, one of Farmer’s main jobs was to, “Basically make sure the screen tower was clear, if any branches or anything got in there, to clean all that out to make sure the screens would keep going.”

The screens are essentially a first line of defense to filter out large pieces of debris in the Ohio River from getting into the intakes.

The screens are essentially a first line of defense to filter out large pieces of debris in the Ohio River from getting into the intakes.

As the clock ticked away, Farmer saw the water steadily rising and captured images from his view at the Tower property.

“When we left on Sunday, out there on the screen tower, it was 31 feet,” he said.

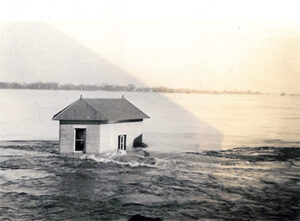

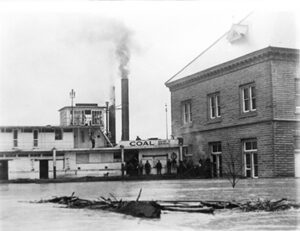

The river finally crested on Wednesday just under 37 feet. When you look at the current river levels in disbelief, it’s unfathomable to think 20 more feet of water is even possible. But that’s exactly what happened in 1937. When the Ohio River crested on January 27, it measured at 57.1 feet.

During that time, Louisville Water encountered serious challenges. To comply with LG&E’s request to conserve electricity, Louisville Water used its own boilers to power pumps. When that started straining the system, Chief Engineer L.S. Vance enlisted help from the C.C. Slider steamboat’s boilers.

During that time, Louisville Water encountered serious challenges. To comply with LG&E’s request to conserve electricity, Louisville Water used its own boilers to power pumps. When that started straining the system, Chief Engineer L.S. Vance enlisted help from the C.C. Slider steamboat’s boilers.

As the men continued working, water filled the building, topping four feet by the time the floodwaters crested. It was a grueling two weeks. At one point, station engineer B.E. Payne sent Vance a radio message saying, “Pumping 20 million gallons a day. Water at windowsills. Send meat, flour, bacon, eggs, clothes, shop taps. Men want to go home for a while.”

As the men continued working, water filled the building, topping four feet by the time the floodwaters crested. It was a grueling two weeks. At one point, station engineer B.E. Payne sent Vance a radio message saying, “Pumping 20 million gallons a day. Water at windowsills. Send meat, flour, bacon, eggs, clothes, shop taps. Men want to go home for a while.”

Things have certainly evolved in almost nine decades, and our crews had time to prepare for the day-long shifts this week.

Things have certainly evolved in almost nine decades, and our crews had time to prepare for the day-long shifts this week.

“We pack our own food. Fortunately, we have a kitchen down there. We have cots in the locker room,” shared Plant Maintenance Mechanic John Booher, ahead of his Wednesday-Thursday assignment. “We’re gonna take power naps.”

This isn’t Booher’s first rodeo so to speak; he knows the drill.

“We go in and we do our initial set of rounds where we inspect everything; check oil levels, check bearing temperatures, listen for any unusual sounds or vibrations or anything like that,” Booher explained.

“The pumps that operate underwater, they have a centrifuge on them. The centrifuge separates the water from the lubricating oil and allows the oil to go back down to the bearings. The centrifuges become clogged up with mud after several hours of operations. At which point, we have to shut it down, tear it apart, clean it, and then reassemble everything and get it back online.”

Booher takes it all in stride. It’s simply part of the job.

A job that Louisville Water is committed to and has a long history of rising to the occasion for, in spite of any challenges, because providing safe, clean drinking water is why we exist.